And it has prompted one of the PSPP’s pioneering efforts – constructing shelter roofs to protect the monuments. The threat posed by moisture is among the most significant for the ancient burial ground. Walking through the site, Matthaei points out monuments that bear clear signs of damage from water, both rain and groundwater, made more severe because of the low elevation of the necropolis compared with that of the city of Pompeii itself. The PSPP has focused on the necropolis, which includes some 73 funerary monuments of varying designs.

“The mission considered that there is no longer any reason to place the property on the World Heritage in Danger List,” says Anna Sidorenko, UNESCO World Heritage Center program specialist.ĭespite the progress, significant work remains for scholars like Matthaei – particularly related to mitigating environmental hazards. The European Union-funded effort has benefited the site in many ways for example, six newly restored homes were opened to the public in December.

Last year UNESCO found that initiatives such as the Great Pompeii Project have begun to turn things around. The collapse received international news coverage, and increased attention was paid to the management of the site amid concerns that more historical structures could be lost. The most notable occurred in November 2010 with the collapse of the Schola Armaturarum, a stone building that featured beautiful frescoes of gladiators.

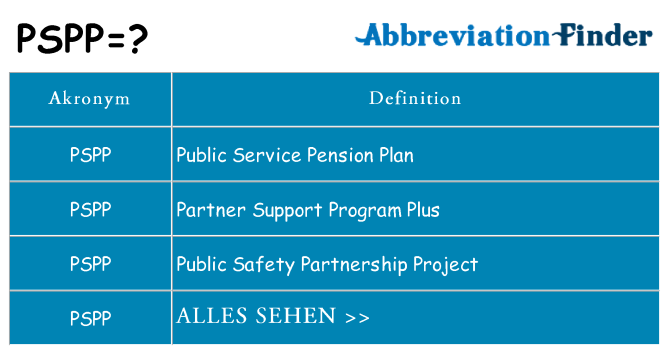

#PSPP PHILADELPHIA SERIES#

But the marvel has long struggled with lack of funding, the negative effects of tourism, inadequate drainage, and a series of collapses of some of its structures. UNESCO, a United Nations agency that seeks to preserve the world’s most important cultural assets, named Pompeii a World Heritage Site in 1997. “For the restoration and conservation sciences, it is a unique city.” “Here you can visit Roman city,” Matthaei says. It now provides an unprecedented perspective on life as it was 2,000 years ago. It has since been a source of fascination, owing in large part to its extraordinary preservation while buried in ash. Pompeii was lost to view for 1,500 years until its rediscovery in 1599. Vesuvius, an active volcano, erupted, leaving Pompeii, the nearby town of Herculaneum, and surrounding villas buried under 13 to 20 feet of ash and pumice. The city was largely destroyed that year when Mt. Thought to have been founded in the 7th or 6th century BC, Pompeii had a population of roughly 11,000 by AD 79 and boasted amenities such as a public water system, amphitheater, and port. “You can bring students there, they can learn, and while learning they can do something.” “There was a lot of work to do, and we thought that would be the perfect place for students to work,” Matthaei says. Between sips of coffee, he recalls meandering with Kilian through the massive site – nearly 160 acres with some 1,500 structures – and realizing that, at the time, no major restoration projects were taking place. “It was kind of love at first sight,” says Matthaei of Pompeii, chuckling, during a conversation in a restaurant across the street from the ruins. The duo met there more than a decade ago as graduate students on an excavation project. Howard Carter: 6 of his first moments in the tomb of King Tutįor Matthaei and Dr. The project also seeks to train young conservators and archaeologists. It aims to not only preserve the famous ruins at Pompeii but to gain new insights into the ancient city. While the PSPP’s staff size is modest, its goals are ambitious. The project, which involves 10 leading European research institutions, is based at the Fraunhofer IBP. Ralf Kilian at the Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics in Valley, Germany, just south of Munich.

Matthaei is coordinator of the Pompeii Sustainable Preservation Project (PSPP), a German-based initiative begun in 2012 as a partnership between Matthaei and Dr.

And that means a fight against the ever-present environmental threats and structural collapses that threaten this historical jewel. His primary objective is to ensure that Pompeii will be around to benefit future generations. “It is a critical part of Western cultural history and therefore the whole world.” Matthaei is unabashedly enthusiastic about the ancient city. As archaeologist Albrecht Matthaei maneuvers his way through the necropolis of Porta Nocera – the ancient burial ground just outside the city walls of Pompeii – there is hardly a monument that he passes by that he doesn’t know something about or hasn’t played some role in helping to preserve.ĭr.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)